The Axioms of Software Development

Even though we have been developing software as an industry for the last 50 or so years, it still seems difficult to predict the outcome of a software project. That was obvious to me as I built my software company.

But I have more than two and a half decade’s experience in both writing software and also managing software projects and teams of developers. I have authored open-source software that’s been downloaded a few hundred million times. Surly by now I should be able to accurately predict a project?

Truth be told, I’m pretty good at it now, but I had to learn it the hard way, with lots of mistakes.

So how do you learn how to co-ordinate clients, developers, investors with time and resources, and ensure your project will be successful and provide a suitable return on investment?

And how I could I teach what I had learned, expensively?

The first step was realising that there are axioms in software development which seem largely unknown and the failure to know them meant we kept making the same mistakes.

Axioms are statements that are accepted to be true. They serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Greek axíōma ‘that which is thought worthy or fit’ or ‘that which commends itself as evident.’

From my perspective, axioms are laws that you can’t really break if you want to stay sane and survive in this environment. Knowing them can ensure you adequately plan and set yourself up for success.

Second step was the realisation that software developers are not the builders of software, they are the architects. I wrote another article about this: What does a software developer do?

Properly understanding the role of a developer gave a solid foundation upon which I could begin to codify the axioms of software development. Understanding these will really help you to control development projects:

The axioms are:

- Desired features will ALWAYS exceed available budget

- Communication is king

- Always consider the return

- Design - Validate - Build

- Be ready to go live

- Ownership & Accountability

- Prefer Stability Over Features

- Stick to your knitting

- Test adequately

- Automation builds productivity

- Maintenance is cheap

I originally thought there was 10, but I was wrong and caught by one of the two hardest things in computing; naming things, cache optimisation, and off by one errors.

So let’s get into this with the Axiom 1.

1. Desired features will ALWAYS exceed available budget.

Anyone that has worked in software development will have experienced this. It doesn’t matter what your budget is. The features you want will always exceed your budget and quite often the available time you have. If anyone doubts this, then go have a look at what the annual expense is for software developers/development at Facebook, LinkedIn or UBER or any large software company.

It doesn’t matter how big you go or how many features you develop, you will always have more features to build than your budget allows. This is a critical thing to understand. Because if you don’t get this, you will often be implementing the wrong thing.

That means, for a product owner, is you will not get every feature you want in the application.

You see, software attempts to mirror the real world in some manner. For example, an on-line store is an attempt to mirror a physical store. In a physical store, you are always rearranging your stock and displays, putting a new sign up or re-decorating. You’re changing your marketing, your staff and a myriad of other items. It’s a constantly changing scene.

The only things that stay the same in this world are things that are dying. If you are not constantly improving then you are dying. There is no third option. There is no such thing as ‘staying the same’. If you stay the same, the world around you is changing and improving. So, in effect, you are going backwards in relation to the world around you. Improving and changing gradually over time can give the appearance of something staying the same, but it is also improving.

Software will always be in this constant state of change as it mimics the physical world.

I sell software development as a service to clients. I also have three or four software applications which I maintain with my staff and I have full-time developers on those applications. I spend a considerable amount of money to keep them updated and relevant. I just keep finding more features to add and our users keep requesting new features.

So, how do we use this axiom of desired features ALWAYS exceeding available budget?

We use this to focus the project and to keep it on-track. The key thing is making a list of the critical features needed for your application? What is critical to make this a successful project?

I’m not necessarily talking about a minimum viable product here. A minimum viable product for many projects can be a sketch on a piece of paper that you can show to someone and say, ‘Hey, if I built this will you buy it?’ That could be a minimum viable product. A sign-up form could even be a minimum viable product.

Decide on features

What I am talking about is deciding on the features to develop and deliver with the software to make it a success? Success could be getting more sign-ups. It could be getting the business off the ground. It could be any factor that determines success for the business.

But you need to be very critical when setting out the critical feature list. It needs thorough evaluation.

For example, client to developer:

Client: Okay, so there’s this feature where if I click on this line-item, it should pop up a window and allow me to edit it. Okay, so that’s a feature, I should be able to edit the line-item.

Developer: But do you really need it to pop-up? Yes, or no?

Client: Well, no. It would be nice if it popped up.

Developer: But is the pop up a critical feature?

Client: No, it’s not. Maybe it’s easier if we just click on the line-item, the page changes and I just edit that form and click save and it goes back to the original page.

Developer: What we are going to do is make this “click, edit a form and then go back to the original page” so that it works as a feature. And, if there’s more money and more time at the end of the project that we have time for we will turn that into a pop-up form for you. We can easily do that once we have the other critical features developed.

You might consider this is not the best possible design, and it doesn’t feel like Facebook or LinkedIn. (Yes, that’s because Facebook and LinkedIn spend untold millions on software development.)

You might say that example is a bit of an overkill, developing a pop-up only takes about 3-4 hours.

Blowing out project time and costs

Sure it only takes 3-4 hours to develop a pop-up, but when you add 2-3 hours twenty times you’ve added 3-4 weeks of development to the project.

That’s the sort of thing that derails any attempt to set proper project estimates and stick to them.

In any estimate a developer looks at the problem from a broad view based on earlier projects they have done and come up with some reasonably accurate guesses on how long it will take to implement the given feature set. They will see ‘be able to edit line-item’ and they can work out it will be about half a day’s work.

But then the developer could be met with the following additional needs:

- It turns out that it needs to be a modal, so then it needs to be a pop-up form on the page. What if the form is larger than one screen? Now we need a pop-up form that scrolls.

- What if it’s too wide? Well, then it needs to be different widths.

- What if I’m viewing on mobile? Well, now the modal needs to be mobile responsive. So, I’d better fix that.

- Oh, but what if they are viewing in Internet Explorer, not Chrome and it doesn’t necessarily support grids at this time. Now we have to create custom CSS.

And on it goes. Suddenly that “simple” modal project went from taking three hours to three days.

These are the sort of things that you encounter as problems.

The most important aspect of the project manager’s job is to whittle down that critical features list to be as bare bones and simple as possible. You can always add features later. There is no limit to when you can add more features.

But you have got to get the thing launched. You have to get it live and you have to get it earning you money.

So this is one of the things we go over with our clients at the start of a project. And it’s the number one thing we look out for.

Features, Budget, Quality

There is a triangle of features, budget and quality. The more money you have, the more of each of those you can have. But if you reduce budget, it’s going to also reduce features and/or reduce quality. So these three items are related in every software build.

They work hand in hand. And really, pick any two. That’s how we describe it to a client and how you can describe its relationships.

But any team is doomed to fail unless it can communicate effectively and efficiently, which gives us Axiom 2.

2. Communication is King

This seems simple, but it’s true and often overlooked. Because features will always exceed available budget, you have to make sure you are communicating enough to overcome that challenge, and thus, the next axiom is “Communication is King”.

Too often I see software projects sending the developer off on their own to build something. The developer comes back two weeks later, and the client says, “Um, that’s not what I wanted.” This shows there is a lack of communication between the developer and product owner for that two weeks.

You must keep communication very, very high between the stakeholders of a software application and the developer. That means lots of deployments and demonstrations while the software is being built. Lots of updates in chat rooms or screen shots of designs and progress.

Whatever works in keeping communication as high as possible

Communication is the most important thing that will derail a project. (Outside of the client expecting all the features for no money.)

If communication drops out, the client starts to feel ignored. They don’t have any reality of what’s going on anymore and because they don’t have any reality of what’s going on, their love of the project will start to drop. In a month or two the whole thing blows up in your face.

We have rules in reinteractive where our developers need to be updating the client two or three times each day on what they are doing and where they are going with the project. This usually is done as follows:

- A morning text update as the developer is starting work “I plan to work on points A and B today”.

- A stand up call with the client (preferably with the video on) to go over any issues or blockers or to clarify things with screen sharing.

- A mid-day update “A is done, I’m now working on B”.

- An end of day update “OK, B is taking longer than expected will continue tomorrow and will get onto C as well. I’m heading off in 15 minutes if you need to ask me anything”.

That level of communication keeps our client engaged and up to date. Some of you might think, “why bother with a morning update if it’s basically the same as the evening?” Well, it turns out that quite often, that overnight, after the developer has stepped away from the task and woken refreshed the next morning, a new way to tackle said problem has materialised. Also, the morning update reassures the client that we are working and active.

We put all of the work we are doing into stories in our task tracking system so that the client sees what’s happening. Clients are constantly reviewing and accepting the various stories through the various changes.

Working out Key Performance Indicators

After finding this axiom on communication, it helped me resolve another problem I had, which was trying to work out the key performance indicator (or statistic) of a developer. I had spent quite some time trying to work this out.

When you go out to the market and ask people what the KPI of a software developer is, you get back answers like ‘hours of coding delivered’ or ‘lines of code’, or something of that nature. None of that really worked for me. Because if it’s lines of code, the way you achieve a better KPI is to just hit return on your keyboard more often and make the lines shorter. “Hours spent coding”, well that’s obviously not the right thing either because one way to increase such a KPI is to get worse at coding so it takes you longer. So, neither was right.

The KPI I settled on is “features delivered and accepted as done”, with no regard to how big or small the feature is. It’s just the number of times a software developer delivers an item of work that is then accepted as done by the client of that project.

This creates a very interesting game dynamic between the client and the developer. The developer will want that KPI to go up as high as possible.

When creating a sign-up form, it will be broken into 10 different stories, 10 sub-features. That’s totally fine. Because that forces the developer and the client to have a higher rate of communication. The client now has 10 features to review and accept on the various aspects of that form and it gives the client more opportunity to say, “Oh - we forgot number nine”. As opposed to ‘Oh, yeah, the sign-up form kind of looks like it works so I’ll hit accept”.

So, it actually increases the communication level between the client and the developer, which is something we very much want, and the client is saying “Yes this is good”, many, many more times during the development process.

The KPI of our developers: “number of features delivered and accepted as done by the customer of the project without regard to the size of the feature”.

What I mean by “without regard to size” is you might have something like, ”implement the dashboard”. The developer might say, “Well, that’s a feature worth 20 points”.

Don’t do that. Don’t assign a different value to different features. Just make every feature worth one point on their KPI. And if you do it that way, the developer will drive the size of the feature down, because they want more points. And that will drive the communication level up with the client who must review and accept each one. It is a great way to keep that communication high.

And keeping communication high is something your clients love. The feedback we receive says they feel they are always in control and know what is going on with their software build.

In a team that has high communication, you are then able to decide on what to build effectively, which leads us to Axiom 3.

3. Always Consider the Return

This axiom is key when working out which features should you develop and in what sequence. This is closely related to the first axiom: required features will ALWAYS exceed available budget. A return can be considered a profit from an investment, be that time, money or goodwill.

In our earlier example, if the feature is created to allow a customer to edit the line-item, then that’s a feature that brings a return. We then have to ask what the return will be for each feature: how much better is the application if it’s a pop-up or an inline edit, thus avoiding a page reload? 50% better or only 1% better?

Just say it works out to only be a 10th of 1% better. Is that worth spending two days building it? The answer is obviously “no”. So, let’s move on and pick the next feature and examine the return it will bring.

As you do this, you’ll find you will start concentrating on the things that really matter in your application. For example, an ecommerce solution is useless without a way to checkout. It’s even more useless if you can’t see a list of products for sale and below that it’s basically worthless if you can not even display a product! So prioritising a smooth checkout flow before you have delivered viewing a product on the site would be out of sequence and detrimental to the project’s success.

While it is an extreme example, ending up with an ecommerce application with the world’s most intuitive, mobile friendly, super fast, high conversion checkout flow, but no way to view and add a product to a cart because you ran out of time or budget, would be a pretty useless ecommerce solution.

As your application becomes more and more feature complete, the incremental return on each new feature will reduce to the point where you are looking at building features that might only make the app one 10th of 1% better. But this is fine, because over time more and more people should be using the application and this 10th of 1% would represent quite a large return from an expanded user base.

Deciding what feature to develop next

In deciding which feature to develop next, you should keep this formula in mind: The Return Value (R) is equal to the Benefit Gained (B) multiplied by the Volume of Use (V) with the Cost to Implement (C) subtracted, or:

Return = (Benefit x Volume) - Cost

While it might be possible to plug in actual numbers and rank a feature backlog precisely, usually there is no need. Just look at your list of features and scan down them and assign each of them a Return Value (tiny, small, medium, large, huge). Then rank these by their return value and you will instantly have the key features you need to deliver first.

This “correct sequence” thinking in terms of return on investment is critical to how you get a project delivered on time and on budget.

Sometimes though, you really want this special feature. It’s going to add some pizzazz to your application, setting it apart from the competition and you are heavily invested in it.

Even in this case, it is still best to put it off until after all the critical features are done first. You don’t have to launch immediately once all the critical features are done. But you CAN.

This is an important distinction.

Being in a situation where your app is ready to launch and you are polishing it with any remaining budget of time and money is a much better space to be in than the budget running out with key features barely started.

Every feature of your minimum viable product must be evaluated based on its return and development must be prioritised on those features that deliver the highest return first.

This may seem pretty obvious but you would be surprised how often it doesn’t happen and you end up with zombie projects that are draining everyone’s will to live.

So once you have decided on what it is you are going to build, how do you go about building it? This is answered in the Axiom 4.

4. Design - Validate - Build

The success of your project depends on validating the plan or idea for your software application BEFORE you invest time and money into building it.

The last thing you want is to find that you have spent buckets of money on something that wasn’t what your users wanted anyway.

When building software, work toward getting some version of the idea or application in front of someone as soon as possible for feedback. Creating this quick mock-up, wireframe, sketch or ideation of what you want to build first and showing it to the end-user is an important initial step.

How fast you can get something in front of the end user and show them the goal of what you are building is proportionate to the potential success of the project.

If the end user can see the final product they will be able to give feedback earlier. Based on end-user feedback, the plans can be easily and quickly altered at the design stage and for a much lower cost.

If you are waiting to get feedback after tens of thousands of dollars of development, you are likely going to end up spending a lot more money because to change anything, first the developer has to undo what they have already built before they can start to do what you want.

Changes cost less the earlier they are made. This is a fundamental truth of design and development.

So Design - Validate - Build is the right sequence, and it is a continuing sequence of constant iteration. The stronger the development team, the faster you can tighten this loop. If you currently only do one of these every month or so, one of your top priorities as a manager should be getting this loop tighter and tighter until it is really flying at a high whirl.

Now that you have your design, and you have validated it, you are now ready to build it, but how long do you wait until you release it to the world? This is answered in Axiom 5.

5. Be ready to go live

In the first four axioms, I covered principles that outline how to approach software development. Now it’s time to get dirty and start coding.

Where do you start and what gets first priority for your development hours?

I decide what gets done first by looking at it this way: In the first 2 or 3 weeks of a project, it should be possible for me to push the application live at pretty much any moment.

That’s right, after a few weeks, be in a state where you can deploy the code to the internet and let users have at it, so both you and they gain some benefit from the software you are developing.

Does that mean the system is DONE in 2-3 weeks? No. But it should have enough features to be live—not necessarily to DO anything useful—but perhaps it has something in place allowing the users of the system to sign in and play with it.

The goal is to start the process of constantly delivering a product, thus allowing the people paying the development bills to “call it” at any time and go live with what they have.

This goes right back to the first axiom – features required will always exceed available budget.

This is why you need to build critical features first.

The goal when you start any software project should be simply: “How fast can we get this thing live?” Even if it doesn’t have enough features to make it really worthwhile, you should have enough features to enable the basic use case to go live as soon as possible.

You need to achieve that as fast as you can.

Because the truth is, your budget could run out at any point, and you don’t want to be left with an application that doesn’t do anything because there are a lot of half-done features with nothing really talking to anything else. You get more benefit from focusing on one key aspect and getting it functioning than you do trying to do everything at once.

Benefits

For instance, my company (reinteractive) built a wonderful site for the State Library New South Wales. We deployed an online platform allowing crowd sourced audio transcriptions of historic audio recordings and published a case study on the process. Their budget was tight. We had only a few weeks to create a transcription platform, load recordings into it and make sure users could contribute.

Four weeks to accomplish something of this magnitude is practically unheard of. But the State Library had chosen the New York Public Library’s Transcript Editor platform as the model. It was an existing open-source project we could fork on GitHub. We figured that an MVP was possible, and we threw one of our best developers at it. Four weeks later, he got the platform live.

And by ‘live’ I mean it was accessible on the internet by users. It was by no means perfect. The first release had the audio recordings practically ‘hard coded’ into the platform — there was no ability for the library staff to add new recordings. But volunteer transcribers could contribute to the historical archives and the first few hundred transcriptions were able to be digitally corrected.

The site was live, and it was in the hands of the users. And it was LOVED! The application in its initial form won an innovation award and based on the initial success, the project gained further financial backing.

In the years since the project launched, we expanded on it and have created new features like the ability of the staff to add recordings to the library without needing a developer. It was a fundamental desired feature but was not required to launch the platform and thus was initially omitted. We have improved the look and feel of the site and the functionality for crowd sourced transcriptions.

But and it needs to be said again, without that initial release on that initial (very limited) budget, the project would never have won the innovation awards it did, nor is it likely to have been considered for further funding of features.

This is a very good example of the benefits of being ready to go live rapidly.

Being ready to go live as soon as possible forces things to get done in a more efficient manner and is a crucial axiom to successful software development.

Getting your project live and in-front of users also helps you demonstrate to your end users and stakeholders that the project is viable. It helps your project gain momentum or keep momentum and interest, so the project does in-fact get completed.

After commencing development, the speed of getting your application ready to go live is directly proportional to the success of the endeavour.

But how do you make sure that the features you develop actually work as intended? This s a key point to ensure you have under control and so our Axiom 6.

6. Ownership & Accountability

Any software project can bog down if the person writing the software is not accountable for the functionality of that software in production.

This is a key factor in getting projects delivered in a timely and economic manner.

It is not in your best interests to have one person write the code and then throw it over the fence to a quality team to see if it works and then over to the operations team who then work out how to get it live. Each step will just report back bugs and incompatibilities and then eventually the first developer gets it back to fix and so on. It’s a highly inefficient use of time for both teams.

The main reason it is inefficient is because of context switching. The developer who wrote it has moved onto the next bug or feature and by the time something comes back, a week or two later, has largely forgotten about all the small little things that had to be taken into consideration to make that feature work.

Tests and documentation can mitigate this, but they are never perfect.

The project flow and assignment of responsibilities by project managers and product owners needs to include that the person writing the code is responsible for running that code in a development or production environment as a fully integrated part of the whole system.

It becomes easier to visualise when we relate this view back to the analogy of building a house in my earlier blog where I outlined the role of a Software Developer. It was there, we realised the software developer role is better associated as the architect and the computer is the builder.

The architect is responsible for all actions to ensure any unforeseen complications are integrated into the project and that the original intended design is achieved. This is not left to the builder or any other parties. The architect is a skilled individual who is experienced at most levels of construction and coordinates the efforts to ensure the original vision becomes a final product that works as an integrated whole.

You want the software developer to own the code they have written, all the way into production.

This creates a huge increase in efficiency.

You are not having to describe things and go back and forth with others.

You are empowering that one developer to take it all the way through to a done and carry that feature all the way through the line.

It also is a great benefit for the developer.

They feel trusted. They feel empowered to fix things. They will originate more if they see something that isn’t right and it just treats everyone in a better state.

The responsibility for the functionality of written software is a pillar of effective software development and, done well, enables faster and more economical development of required features.

With this axiom in place, your speed of delivery will increase, but you have to be careful not to jump on the feature gravy train and just keep pumping out those sweet, sweet features, it’s important to not let your technical debt get out of hand which is why we need Axiom 7.

7. Prefer Stability Over Features

The theme here is that you need an application that performs the core features well, not an application that does a multitude of functions in a really buggy way.

Nothing will turn off end-users more than an application that can’t do what it says it can.

This comes back to that first axiom – desired features will always exceed available budget.

So, you really want to identify: what are the key aspects of this app that absolutely need to work? This is sort of a Minimum Viable Product. And then focus on the points that make up that MVP. Really it comes to the desired features exceeding budget idea and getting those critical items out first.

But it also comes into play when you launch. Just because you’ve built a feature doesn’t make it stable and usable, and it doesn’t mean it will perform under load.

You need to build in some time to go and do some bug fixing because it doesn’t matter how well you develop, you will always find some bugs in any software application, it’s just inevitable.

In many cases, bugs are just unimplemented features.

An example I ran into of this was relating to recording a value over set periods, and changing the frequency of the report.

When first building it out - you enter a value every Friday and the application takes that value and saves it. On a weekly basis you could look at a graph and you would see the average value increase or decrease week-on-week. It would look correct.

But, then you realise there is a benefit to viewing this information with monthly totals. So, you filter the values and take the sum of values recorded in April as one data point and the values from June as the next data point and so on. But wait, every second month, it seems like there is five times the average weekly value instead of four times. You realise that it doesn’t look right because in April there was less activity, but the value is higher.

You ask the developer why this anomaly, and they say “Oh, that’s because we are only recording the value every week and in April, there are five Fridays but in February there are only four. And the extra Friday that is in April is just the first day in April, so all the values of the other 6 days that make up that week are being counted in April, when they really belong in March.”

Immediately you think – that’s a BUG! This is unusable. We must fix it! It is stupid.

Actually, no, it isn’t a bug, it is just an unimplemented feature. The unimplemented feature is when you are entering a weekly value, if that week spans two months, the system needs to be smart enough to recognise that and ask the user if they want to split the value over two months.

This is where you might start to look at bugs and features in a new light.

Sometimes there are genuine bugs, the system is simply doing the wrong thing.

Usually it is because the feature has not been developed enough to handle the edge cases of the real world. Software is generally an attempt to replicate the real world and the real world is not black and white. There are lots of grey areas in the real world.

So, software has to have ways to handle that. A computer can’t intelligently figure it out on its own, because a computer is not intelligent. All computers get any apparent intelligence from their Human creators.

So, it is ideal to prefer stability over features wherever possible.

This isn’t to say that everything should be perfect before exposing customers to your platform. There is definite value in the idea that: “We need to get something running so that we can get some traction.” But, just be aware if you do a push to rapidly get some features out, you need to include in your plan going back to pay down that stability or technical debt on the project and make the features more stable.

On my own software-as-a-service projects, I regularly tell my developers that I need them to spend three days fixing whatever they know needs fixing. Go to the bug tracker and close off some bugs, do some re-factoring for performance or stability.

If your developer knows their stuff they will know the bottle-necks in the system that need the architecture tweaked a little, or code that can be cleaned up to be more efficient and stable. I tell them to go for it.

Every bug to a developer is also a stability issue and something that they don’t like and want to fix.

But sometimes you and your development team see a bug, or a piece of dependent software that just NEEDS to be fixed, this can then cause you to run down all sorts of rabit holes and loose focus on what is important, delivering your product, and so we have Axiom 8.

8. Stick to Your Knitting

“Stick to your knitting”, is an idiom. It loosely means; Do what you’re good at and what you know. Don’t dive into fields that aren’t your expertise.

For example, If you are building an eCommerce solution, don’t try and build an entire payment provider hooking into the credit card network as part of your eCommerce solution. It just doesn’t make sense to try and handle this complexity. Not at least until you are doing billions of dollars in transactions! Just stick to building what is special to you and what you need to go live.

This can also happen at the smaller scale. Need some marketing automation? Well, hook it into a marketing automation solution and use the tools provided there, don’t try and build it yourself.

Out-source as much as you can to other proven software platforms. If you need to upload files into the system, use Amazon S3 or Google Cloud Storage – don’t try and build an entire file hosting service, even if file hosting is core to your business. A great example of this is Dropbox. They built their entire business on top of S3 and only started building their own solution when they had 500 peta bytes (500,000,000 gigabytes) of data being hosted.

These are obvious examples, but it is easy to fall into the “I’ll just build it” trap.

The problem with “I’ll just build it” is that you under estimate the complexity of the edge cases that exist in the problem domain. Sure, building a file server for a bunch of files might seem easy, or a simple marketing workflow email system might be ok, but as soon as you start wanting more features, the complexity grows and you are stuck now with a home built solution.

Bluntly, there is a reason these established companies have spent millions of dollars in developing their platforms and solutions and you don’t have the development budget to build features that duplicate their functionality.

Spend that money on YOUR features that make you unique.

Stick to building what is important for your app and use existing proven software for the added functions you need. Develop with software that allows use of external libraries so you’re not having to re-do work that someone else has already done.

We have found we can integrate almost any system into your app.

I have focused on Ruby on Rails for the past 14 years for this reason. With a couple of hundred thousand gems (code libraries) that you can use to add functionality to your application.

With such a widely used and supported community of support, it allows you to code only what is needed for your specific application and 95% of code to support common functions are available to rapidly implement, this is one of the reasons I prefer Ruby on Rails.

So stick to your own knitting and make sure that your core code works as intended. How do you make sure it works? Axiom 9.

9. Test Adequately

Arguably, the ‘best’ way to test a modern web application would be to have a person sit down in front of a computer with a list of features that the web application should be able to do, and to click around the application and try to complete the tasks required while using each of those features, while inspecting the result to see that it was done correctly.

However, as the number of features rise, this rapidly becomes impractical. For a tiny application, someone might be able to test all the features in a day or so of work, but any large application would take months (or years!) to click or type through every feature.

This would also be extremely tedious, repetitive, boring, high precision work as the vast majority of the time everything would just work correctly, and humans are really not very good at tedious, repetitive, boring, high precision work.

Computers, however, are really good at tedious, repetitive, boring, high precision work. A modern computer will calculate 2+2 and make sure it equals 4 probably a billion times a second if you asked it to. It would do this without complaint. If 2+2 didn’t equal 4 for some reason one time out of that billion, it would tell you that it happened without fail.

So, in order to test a web application, we build a second piece of software (called a ‘test’ or a ‘specification’) which confirms the feature they just wrote works as intended. This is quite often achieved by simulating a user clicking and typing around on the website, inspecting the results shown on the screen and checking what is saved in the database.

As you can imagine, with thousands of features, you would need to (and do) write thousands of tests. But for every single feature, there may be one or fifty ways to use that feature. Should we write tests for just one method? Ten of the methods? Or all fifty?

Obviously writing more tests results in more stable code. But there are other drawbacks, not the least of which is the expense of paying someone to write them!

So this then raises our next question…

What is the Goal of Testing?

Software will have bugs as it’s being created. This is a known fact. The amount of money spent to make bug free software for critical systems like aircraft or spacecraft or medical equipment, is not a viable option for your average web application.

To make a web application to be near 100% bug free at all times would inflate the price perhaps thousands of times over. At that point, you wouldn’t be able to afford to build it.

This is especially true when you realise that what one person might be calling a software bug can sometimes be described by another as an unimplemented feature or even an actual bona fide feature!

You can complicate this further by considering all the bugs that could possibly arise due to the end user operating system being out of date, or browser errors, or their internet connection being flakey, or if a third party API your application depends on fails, or even bugs arising from your software being so popular that it runs into scaling issues.

So ‘bug free’ can not be the goal. At least not in the real world.

Therefore, if ‘bug free’ is not the goal, what should the goal be?

This is hard to quantify. I have always promoted the idea that we should strive to make sure the common paths travelled by the end user through the application are as bug free as practically possible.

If there is a bug that arises sporadically in 1 in about 100 requests, this might be able to be lived with if that feature is only used once per month by each user. Most users would then never even encounter the bug.

So this gives us the idea of “testing adequately”. You want to test for what we call “the happy path”. If everything is going right, this is what the software system should do. You don’t want to test every individual line item of the code, that would be ridiculous, and no one has the money to do that.

Adequate tests allow developers to look forward, not back when they build out new features for your application. Any incompatibility between old and new features is immediately visible and the exact incompatibility can be rapidly pinpointed by either fixing the test to include the new functionality, or fixing the new functionality to make the existing test pass. What to Test?

Modern software developers do not write every line of code in the software they develop. They use frameworks like Ruby on Rails with tens or hundreds of software libraries (gems) they call on to perform specific functions. This speeds development. It means a developer only has to write the code to achieve your individual needs. Pre-existing libraries can handle routine functions like user authentication, reading and writing from databases, correctly forming emails or integrating with payment providers.

So this gives you the first clue on what to test, and that is “test the code you write”. If a developer includes a whole software library that correctly formats an email, then they should not be writing tests to make sure the email was formatted correctly. What they should test is the contents of the email, that it is being sent to the correct person, that the subject is correct and so on.

OK, now you know that you only write tests for the code you write, we are faced with the problem of WHICH code deserves a test?

Testing every piece and possible combination of the code would be impractical if not impossible. We need to select the best code to test.

I recommend breaking this down into two broad categories.

First, test any complex algorithms or calculations with valid and invalid inputs checking their outputs. If you wrote a complex set of code around calculating the correct taxes and tariffs, then multiple combinations of this (including negative values) would be very smart to test thoroughly. These tests are cheap to write and run both from a computational and developer time expenditure and so you should be thorough.

For the more complex features, like API integrations to external providers, or the usability of the site (clicking around and doing things) it is best to first test what we call the “Happy Path.” This is the path that most users are going to take if nothing strange is going on. With the Happy Path and complex calculations tested, you give your developers (and any other developer who might encounter the code-base in the future) great confidence they are not creating new problems when adding new features.

When Website Requirements Evolve

Let’s say we write a piece of software that dictates: before a user can sign up to this service, we have to check that they live within a specific area.

And later, you implement a change in the system that allows people from another area to sign up. So, with the revised condition, your developer implements the change allowing people from a second area to sign up. In the intervening months/years since the initial requirement, you have taken on a new developer who wasn’t around when the original code was written. He might not be aware that there was a requirement that sign-ups be only allowed in certain areas.

The new developer thinks that this isn’t a problem and goes ahead and tries to implement the new feature. Once the new requirements are implemented, if there was a test written around the original requirement, the system will return an error saying: “warning, this new requirement violates the previous requirement”.

At that point the developer can go “Oh, I know why that is” and can go and fix it, or they can come back to you as a stakeholder and say, “hang on a sec, there is a requirement here about only allowing users from this location to sign up. Is the requirement no longer valid? Or is that earlier requirement only valid if another condition is met?”

You, as the software stakeholder, will be able to clarify: “The location requirement is only if they want to purchase these products. Add an additional check on the location requirement to check what product they are buying.”

The developer then easily adds an additional check and the matter is resolved. If you didn’t have tests, your developer likely wouldn’t know there was an incompatibility with the function he implemented. The new change would go into production and no one would know that the location requirement has been broken. You would then end up (in this fictitious example) with products going to the wrong customers.

As your Website Grows, Complexity Grows

The above example covers one requirement. But when you view modern software applications you quickly discover there are tens if not hundreds of requirements that the software must do to reach the intended result. For example, when a user clicks a critical button, it should achieve a specified result. Or, if a user loads a page, tests could confirm the correct content is loaded. Or, when a user logs into their account, they see their account information and they can achieve the purpose of their visit.

With the complexity of modern software, a comprehensive set of tests will ensure that any change made alerts users to any unintended effects on other parts of the code base.

When Things Go Wrong

The other scenario that comes up often is a user ends up doing a certain sequence of things that results in the system crashing because they have managed to get the system into an unknown, untested and undeveloped state.

In this situation, the developer would reproduce this error, write a test around that error and then fix the code to do the right thing in that specific state.

This way, as the system grows, you get a more complete set of tests that makes sure everything is working as intended.

Adequate Testing Delivers Speed

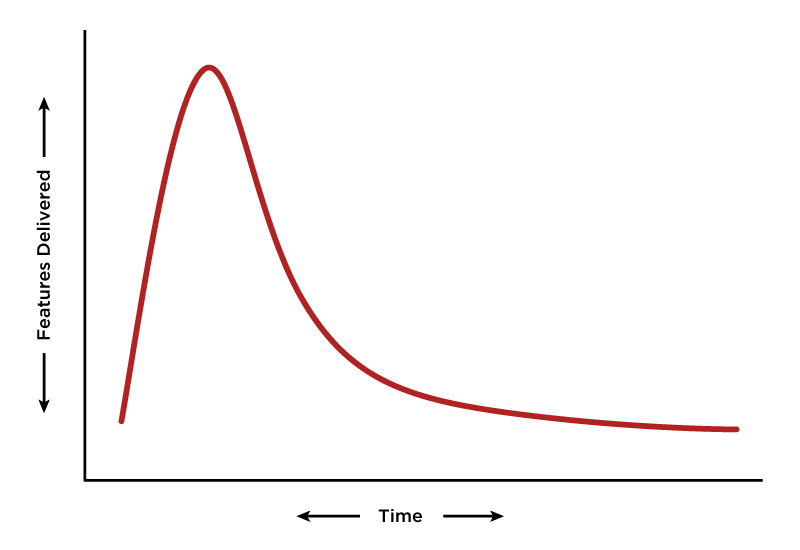

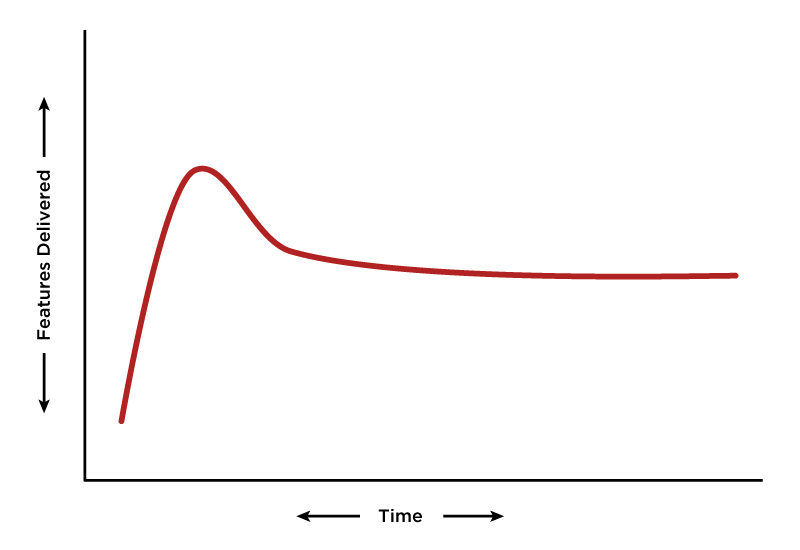

With the above in place you end up developing at a more consistent pace. Development teams that do not test, generally have a large spike of features delivered early, but the features delivered over time drop off rapidly as each new feature ends up breaking something else without them knowing and they are constantly fighting fires of broken production systems due to unintended changes.

Teams that test adequately are initially slower off the mark, but their delivery over time stays more constant providing with a greater number of features delivered over the life of the project.

This speed over a long term really compounds allowing you to continue to ship at a rapid pace over many years. So how else can you increase your speed if you are doing this correctly, automation!

10. Automation Builds Productivity

While I’ve listed this as an axiom of software development, really, this is true of all industries. Anything you can properly automate will result in less errors and higher productivity.

In order to do this, you first need to understand a fundamental of automation. You can not automate something that has not been standardised to be done the same way each time or done in accordance with a strict set of rules.

A mistake I have seen made many times is attempting to automate a process that still has numerous edge cases, hours are spent on getting the automation done just to realise that there are occasions where the process needs to be different requiring decisions to be made in order to proceed.

But once you have a process that happens the same way every time according to a set of rules, then this is ripe for automation and you should automate it as soon as practically possible.

In a software development world, automation can be achieved in many places, from task management, building, testing, deployment, and even to monitoring and scaling. We’ll go over a few of these here to give you some ideas on where you can automate your processes.

Automate your Tests

Picture what happens when your developer creates a new feature. It makes total sense to you.

You look at the feature on staging and it looks good. So you approve it to go to production.

But, when you go to deploy it, your automated test process comes back with an alert saying, ‘We just found an error on the 6 ft requirement for the basketball team members.’ Your automated testing process stops the deployment process. You are very lucky that the automation process caught that error before it went live. You are left with a choice of either fixing the error or fixing the test to push the code live.

Automate your deployments

When you deploy code to your production environment on an application that is going to have continuing work, you don’t want someone manually copying files onto a server. You equally don’t want someone running a 10-step manual process.

You want to automate that as much as you can.

A big reason to automate is that it makes deployments easier. And it creates the functionality to roll back deployments, if you happen to push an error into production.

Rolling back your production environment

Another scenario you might encounter is having a feature pushed to production that everyone is happy with. But later finding one subset of users report that the new feature breaks the part of the system they use - and now they are blocked. With automation, you can just roll that back and put the old version live, quickly and easily.

I unknowingly created this exact issue. Because I’m both a software developer and the project manager of my own software projects, it’s pretty easy for me to write what’s called “founder’s code.” Essentially, that’s sub-par code which I think is good enough to just push live. (I don’t do it as much now as I used to.)

One day I did an update, and believe it or not, I was updating the copyright year in the footer so it shows the current year. That is pretty obvious. But of course, I was being smart! I didn’t want to just edit the year in the text, I wanted it to automatically update so I wouldn’t have to fix it every year. So, I wrote some “founder’s code” that automatically sets the current year as the copyright year and I pushed it live. And I promptly went out for dinner around 7pm, without taking my mobile phone.

I got home a couple hours later and I had at least 10 messages from different clients, complaining about the application. My email inbox was flooded. All sorts of things.

As it turned out, I had pushed a syntax error into production that only came up in a certain way and it caused the application to crash.

Luckily, our entire process was automated using the OpsCare Service, which monitors all our applications 24/7. When my OpsCare team saw that I had pushed something into production right before the site went down, they first tried to contact me and, after failing to reach me, they just pressed a button and the whole thing rolled back to a previous version and the whole system came back up again.

The total downtime was perhaps 10 minutes, instead of 3-4 hours, which was the time I was out at dinner.

With your systems automated, it will allow you to continue to deliver and grow your product, but invariably I have found that clients continue to deliver features, without continuing to maintain the underlying systems, this leads us to the final Axiom 11.

11. Maintenance is Cheap

What do I mean by maintenance is cheap? I mean that the money you spend on maintenance is like an early payment on a loan, those payments earn interest and return much bigger dividends into the future than the initial investment.

Lets have a look at two extreme examples to clarify this.

The first project has no maintenance done. No upgrades. No security patches. No updates to the infrastructure running it. Nothing. While this will run quite happily, maybe for years, one day something will have to be done to keep the system running, and at this point, any developer starting on it will have a massive uphill battle even to get the application in a state they can even start developing on it. Not to mention as each month without maintenance goes by, the security risk of a data breach or other problem just exponentially increases. I have seen applications like this where it was cheaper to completely restart the application in the latest versions of the underlying system and porting over the business logic resulting in spending more than the initial investment of writing it in the first place.

The second project has regular maintenance done on it. Every month a little bit is done, a bug fix here, a security upgrade there, an operating system update over there. Over the years this system is kept broadly in sync with the movement and changes to the software development landscape. When the time comes to add a new feature, any developer can rapidly get the system up and running and make the needful changes in a short period of time.

Obviously maintenance does not come for free, but there are many companies out there (including reinteractive :) that provide maintenance services for all sorts of applications where you do something like purchase a block hours each month to keep your app up to date and functional.

What are the risks of no maintenance?

The risks of not maintaining your system include:

Data Breach - your system might have a security vulnerability from the code in your application or one of the dependent software libraries it uses that results in some or all of your users data being exposed and then sold to the highest bidder. I don’t think a week has gone by recently without a major data breach, and a majority of these are caused from out of date and unmaintained software.

Data Loss - your system could end up having a bug that just deletes data. Or has a flaw that allows an attacker to delete that data, causing your users and your company data loss requiring expensive restore processes (both in time and money).

Performance Degradation - an unmaintained system will eventually slow down as the database it is using grows in size and no performance work is done to handle this additional data.

Integration Failures - even if your system is perfect, it probably interfaces with other systems in some way or another, these other systems will be constantly improving over time and updating their APIs and processes. Without performing regular updates, your system will be left behind and eventually be unable to integrate with the systems it needs to.

Hijacking - This is where an attacker finds a flaw in your system that allows them to impersonate your users, or use your system in unintended ways that results in your site becoming a source of SPAM. One of our clients had a WordPress site that was not maintained (and it is now!). They used a compromised plug-in which was hacked. The compromised plugin sent out an email to their entire contact list with links to hard core pornographic sites. The breach, while not being particularly expensive to fix, cost them greatly in damage to their reputation, brand management and trust. Something that just wouldn’t have happened if they had a maintenance plan in place taking care of the points above.

Environment Rotting - Software itself doesn’t rot, but modern software is built on a stack of other products, all of which get updates and get improved over time. Without maintenance, it can become almost impossible to even start the application for a new developer as all the tooling that was used to build the application in the first place has changed drastically or become unsupported altogether. In addition to this, the ecosystem of blog posts, help articles and the like have all moved on to newer versions making finding the cause of some weird bug even harder to find for your development team.

Morale - Finally, the morale of your team is impacted. They see this system that they worked hard on, get neglected and left behind. Then when they are inevitably asked to fix something that’s broken, everything has to be done under a time crunch with them trying to get this application running that hasn’t been developed on in years with all the team members that built it originally long gone and no one left to know how the thing even starts.

Imagine you are the driver for some car company, and the car your are assigned has no maintenance budgeted to it? You do your best to wipe down the dash and make sure you leave it out in the rain for a wash, but after years of driving, the oil would be fouled with contaminants and possibly have caused damage to the engine. If one spark plug had failed, that would have fouled that cylinder. The brakes would probably need replacing, in addition to major maintenance probably being required on the overall car. Aside from the fact it would probably be a death trap to drive, getting it fixed would be a very expensive nightmare.

Software projects often cost many times the cost of a new car, yet the idea that you would leave a new car without maintenance for years would be considered ludicrous.

Getting your software system maintained regularly is very much cheaper than leaving it to rot and break over time, even without the developer costs factored in, it can be seen as a cheap form of insurance to avoid expensive settlements, suits, blackmail costs etc due to negligence caused from criminals trying to attack your system for their profit.

What needs to be maintained?

The key points to maintain are:

Security Vulnerabilities Found Software Patches Database Maintenance (ie. vacuuming, health checks, and log management) Updating dependencies, plugins, libraries and language Updating underlying software versions to ensure continued support. Updating the infrastructure (operating system, servers etc) Updating the documentation on how to use it Adding more tests around core functions Improving how a new developer can get up to speed

Every modern software system contains dozens to hundreds (sometimes thousands) of dependent libraries in addition to the code that was written in the application itself. No matter how big or small your application is, maintenance is required to keep it healthy and functioning and safe.

As in life, in software there is no such thing as a static, steady, always the same, existence.

If something is not being improved and kept up, it will decay and eventually cease to operate if only because everything around it will continue to be improved and grow leaving your system behind.

Time and money spent on maintenance to keep your software up-to-date will ensure you don’t encounter a nasty surprise later when it ceases to perform the functions it was designed to do.

In Closing

The above axioms were learned through years of running a software consulting company, and hard won through many expensive mistakes.

I hope they help you with your next project.